Black Ice spoken word “Imagine” is his take on how the lack of opportunities in the inner city deprives young men and women of a positive self image and self respect.

https://youtu.be/8kVT89O6cLo

Imagine

What happens in neighborhoods where the self esteem

has been over shadowed by the decay

and the children no longer play the way they used to.

Where young boys choose to follow figures that had no father figures.

A place where lives have been reduce to mere names on a nigger wall

a lot of dead shames on a nigger wall

‘cause most of my childhood friends died over some dumb shit.

It’s like we all on some slum shit

what happened to that “We Shall Overcome” shit?

Nigger, where I’m from, shit, they done torn down the projects

and took away neighborhood sports.

It’s a place where little black boys put on jerseys and shorts.

Dream big about stardom on fine hard wood courts

but await to the harsh reality of the strip unfinished inner city floor

where life splinters.

Cold winters are sheltered by crack houses

instead of recreation centers that they claim to not have the paper

to keep open for operation.

The deconstruction of the black family has been in

perpetuation ever since Willie Lynch has set his theory in motion.

Decharacterization was his sole promotion.

Therefore, if you take the basketball out of his face and

put the coke in its place he’ll still score.

What’s a young boy when he doesn’t want to do wrong but there’s

a lock on the right door.

When he has the heart of a soldier, the aggression of a prize fighter

but no one has taught him what to fight for, see

most our families are fatherless and quite poor.

So we miss out on meals as well as kisses and hugs

you’ve got the audacity to cut the funding for the

facilities to keep us off the streets

then ask us Why we sell drugs?

But imagine if niggers put down their dice and guns

and picked up their daughters and sons and

put a little love right there where the hate is.

Imagine if niggers had chance to become accountants

before being taught what the difference between wet and dry is.

Imagine if these little inner city kids had the same type of schools

as these little rich kids had way out there in the sticks.

Imagine if niggers had the chance to

learn chemistry for real before we learn how to whip 7½ out of six.

Imagine if these little black girls could go to these dance schools for free

and learn to love the dream of that Broadway show.

Imagine if she wasn’t forced into a game where you assume a

filthy name to put your soul and ass up for show.

Imagine she was taught to love herself, imitate no one,

demand and demonstrate respect when she walks though the door.

Imagine if she watched the tellie and saw herself during the prime time hour instead

of the four o’clock video whore.

Imagine.

Thursday, October 27, 2016

Wednesday, October 05, 2016

Ick! 7 germy spots around the home

Ick! 7 germy spots around the home

|

So you might have a guess or two about where germs tend to lurk in homes. See a few hot spots below — some may surprise you. So you might have a guess or two about where germs tend to lurk in homes. See a few hot spots below — some may surprise you.Prime places for germs Of course, there are lots of objects, nooks and crannies in the average home that may harbor germs. In fact, there are too many to mention here. So, let's focus on a few that you won't want to miss. Make a habit of regularly cleaning these items to reduce your exposure to germs, including those that can cause illness. 1. Kitchen sponges and dishcloths. They pick up germs and spread them. Since they're often damp, they're also perfect breeding grounds for bacteria. Quick tips: You can actually zap a wet sponge in the microwave for one to two minutes to kill germs — or run it through the dishwasher. Use clean dishcloths or paper towels. Wash dish towels and rags in the hot cycle of your washing machine. 2. Toothbrush holders. In your normal routine, you may forget to wash these. But remember this: They're often placed near flushing toilets, which can send germs flying. Quick tips: Scrub toothbrush holders with hot soapy water. If you use a cup or other freestanding holder, put it through the dishwasher once or twice a week on the hot cycle. 3. Pet bowls and toys. You don't want to fetch bacteria, yeast and mold during playtime. Quick tips: Wash bowls and hard toys with hot soapy water. Toss soft toys in your washing machine on a hot cycle. And always wash your hands after playing with household pets — especially before eating. 4. Countertops and cutting boards. These frequently used surfaces need on-the-spot attention to stay clean. Quick tips: Clean countertops with hot soapy water, especially before and after preparing food. After each use, wash cutting boards. To avoid cross contamination, always use separate cutting boards for fresh produce and raw meat, poultry or fish. 5. Knobs and handles. Items people touch frequently tend to get germy. Quick tips: Clean doorknobs, toilet handles, faucets, etc., often with hot soapy water or disinfecting wipes — especially if someone in the household is ill. 6. Coffee makers. Their water reservoirs make damp, cozy homes for bacteria to multiply in. Quick tips: Follow the manufacturer's directions for your coffee maker. Most advise cleaning every 40 to 80 brew cycles — or at least monthly. 7. Finally … the kitchen sink. It's last, but certainly not least. The sink can harbor germs from all sorts of sources, from dirty sponges to grimy pans. Quick tips: Wash the sides and bottom regularly with hot, soapy water. And don't overlook the strainer in the drain— clean it too. You can also use a mild water-bleach solution* or other sanitizing solution to clean some items, such as sinks, countertops, cutting boards and pet items. Rinse in clean water — and dry. |

Friday, September 30, 2016

Demagogue: The Fight to Save Democracy from Its Worst Enemies

by Michael Signer

A demagogue is a tyrant who owes his initial rise to the democratic support of the masses. Huey Long, Hugo Chavez, and Moqtada al-Sadr are all clear examples of this dangerous byproduct of democracy. Demagogue takes a long view of the fight to defend democracy from within, from the brutal general Cleon in ancient Athens, the demagogues who plagued the bloody French Revolution, George W. Bush's naïve democratic experiment in Iraq, and beyond. This compelling narrative weaves stories about some of history's most fascinating figures, including Adolf Hitler, Senator Joe McCarthy, and General Douglas Macarthur, and explains how humanity's urge for liberty can give rise to dark forces that threaten that very freedom. To find the solution to democracy's demagogue problem, the book delves into the stories of four great thinkers who all personally struggled with democracy--Plato, Alexis de Tocqueville, Leo Strauss, and Hannah Arendt.

https://www.amazon.com/Demagogue-Fight-Democracy-Worst-Enemies-ebook/dp/B0023ZLNOC

Tuesday, September 13, 2016

It Pays to Increase Your Word Power

Does your lexicon need a lift?

Here are a few words from Talk Like a Genius by Ed Kozak

capitulate (kuh-'pih-chuh-layt) v. - stop resisting.

Only when I wrapped the pill in bacon did my dog finally capitulate.

unequivocal (uhn-ih-'kwih-vuh-kuhl) adj. - leaving no doubt.

The ump unleashed a resonant, unequivocal "Steee-rike!"

cavalier (ka-vuh-'lir) adj. - nonchalant or marked by disdainful dismissal.

Our driver had a shockingly cavalier attitude about the steep mountain road ahead.

leery ('lir-ee) adj. - untrusting.

Initially, Eve was a touch leery of the apple.

levity ('leh-vuh-tee) n. - merriment.

Our family thankfully found moments of levity during the memorial.

penchant ('pen-chunt) n. - strong liking.

Thomas was warned repeatedly about his penchant for daydreaming in meetings.

bifurcate ('biy-fer-kayt) v. - divide into parts.

If anything, Donald Trump has certainly managed to bifurcate the nation.

craven ('kray-vuhn) adj. - cowardly.

She took a markedly craven position against the weak crime bill.

coterie ('koh-tuh-ree) n. - exclusive group.

Claire's coterie consisted entirely of fellow Mozart enthusiasts and violinists.

stalwart ('stahl-wert) adj. - loyal.

Throughout the senator's campaign, Kerrie has repeatedly shown stalwart support.

travesty ('tra-vuh-stee) n. - absurd imitation.

Her lawyer demanded an appeal, calling the jury's decision a travesty of justice.

hedonism ('hee-duh-nih-zuhm) n. - pursuit of pleasure.

In Shakespeare's Henry IV, young Prince Hal mistakes hedonism for heroism.

obviate ('ahb-vee-ayt) v. - prevent or render unnecessary.

Gloria's doctor hoped that physical therapy would obviate the need for more surgery.

excoriate (ek-'skor-ee-ayt) v. - criticize harshly.

Coach Keegan was excoriated by the media for the play calling during the game's final minutes.

penurious (peh-'nur-ee-uhs) adj. - poor.

Paul and Carla entered the casino flush and left it penurious.

If you track down the origins of intelligence, you find the Latin inter ("between, among") plus legere ("choose, read").

To be intelligent, then, is literally "to choose among" or "discern."

The versatile legere also gives us the words legend, lecture, election, and logo.

Here are a few words from Talk Like a Genius by Ed Kozak

capitulate (kuh-'pih-chuh-layt) v. - stop resisting.

Only when I wrapped the pill in bacon did my dog finally capitulate.

unequivocal (uhn-ih-'kwih-vuh-kuhl) adj. - leaving no doubt.

The ump unleashed a resonant, unequivocal "Steee-rike!"

cavalier (ka-vuh-'lir) adj. - nonchalant or marked by disdainful dismissal.

Our driver had a shockingly cavalier attitude about the steep mountain road ahead.

leery ('lir-ee) adj. - untrusting.

Initially, Eve was a touch leery of the apple.

levity ('leh-vuh-tee) n. - merriment.

Our family thankfully found moments of levity during the memorial.

penchant ('pen-chunt) n. - strong liking.

Thomas was warned repeatedly about his penchant for daydreaming in meetings.

bifurcate ('biy-fer-kayt) v. - divide into parts.

If anything, Donald Trump has certainly managed to bifurcate the nation.

craven ('kray-vuhn) adj. - cowardly.

She took a markedly craven position against the weak crime bill.

coterie ('koh-tuh-ree) n. - exclusive group.

Claire's coterie consisted entirely of fellow Mozart enthusiasts and violinists.

stalwart ('stahl-wert) adj. - loyal.

Throughout the senator's campaign, Kerrie has repeatedly shown stalwart support.

travesty ('tra-vuh-stee) n. - absurd imitation.

Her lawyer demanded an appeal, calling the jury's decision a travesty of justice.

hedonism ('hee-duh-nih-zuhm) n. - pursuit of pleasure.

In Shakespeare's Henry IV, young Prince Hal mistakes hedonism for heroism.

obviate ('ahb-vee-ayt) v. - prevent or render unnecessary.

Gloria's doctor hoped that physical therapy would obviate the need for more surgery.

excoriate (ek-'skor-ee-ayt) v. - criticize harshly.

Coach Keegan was excoriated by the media for the play calling during the game's final minutes.

penurious (peh-'nur-ee-uhs) adj. - poor.

Paul and Carla entered the casino flush and left it penurious.

If you track down the origins of intelligence, you find the Latin inter ("between, among") plus legere ("choose, read").

To be intelligent, then, is literally "to choose among" or "discern."

The versatile legere also gives us the words legend, lecture, election, and logo.

Thursday, July 28, 2016

There Goes the Neighborhood - Is Gentrification Really a Problem?

Is it really

a problem when poor areas get richer?

What the

American ghetto reveals about the ethics and economics of changing neighborhoods.

by Kelefa Sanneh - The New Yorker, July 11 & 18, 2016

At the Golden Globe Awards, in January, Ennio Morricone won Best

Original Score for his contribution to “The Hateful Eight,” the Quentin

Tarantino Western. Accepting the award on Morricone’s behalf was Tarantino

himself, who brandished the trophy in a gesture of vindication, suggesting that

Morricone, despite all the honors he has received, is nevertheless underrated.

Tarantino proclaimed Morricone his favorite composer. “And when I say favorite

composer,” he added, “I don’t mean movie composer—that ghetto. I’m talking

about Mozart. I’m talking about Beethoven. I’m talking about Schubert.” The

backlash began a few moments later, when the next presenter, Jamie Foxx,

approached the microphone. He smiled, looked around, and shook his head

slightly. “Ghetto,” he said.

Tarantino’s comment, and Foxx’s one-word response to it, became a

big story. In the Washington Post, a television reporter called Tarantino’s

“ghetto” comment a “tone-deaf flub.” A BBC headline asked, “IS THE WORD

‘GHETTO’ RACIST?,” and the accompanying article summarized the thoughts of a

Rutgers University professor who accused Tarantino of implying that “the ghetto

was not a place for white, European, male composers.” Of course, “ghetto” is

itself a European term, coined in the sixteenth century to describe the part of

Venice to which Jews were confined.* And Tarantino, in suggesting that the

category of film composition was a ghetto, was using a common dictionary

definition: “something that resembles the restriction or isolation of a city

ghetto.” But “ghetto” is also an idiomatic way of dismissing something as cheap

or trashy. And the adjectival “ghetto” owes its salience to the fact that a

modern American ghetto is not only poor but disproportionately

African-American. Recent census data showed that 2.5 million whites live in

high-poverty neighborhoods, compared with five million African-Americans.

Earlier this year, Senator Bernie Sanders went further, saying, “When you’re

white, you don’t know what it’s like to be living in a ghetto.”

What is a ghetto, really—and who lives there? In “Dark Ghetto,”

a pioneering 1965 sociological study, Kenneth Clark depicted Harlem, a

paradigmatic ghetto, as a “colony of New York City,” defined by both its

economic dependence and its segregation. In the decades that followed, scholars

argued over the limits and the utility of the term— did it apply to any poor

neighborhood, any ethnic enclave? The word may have various definitions but it

arouses singular passions, which is why, in 2008, the sociologist Mario Luis

Small suggested that his colleagues stop using it altogether. He argued that,

in many ways, “poor black neighborhoods” were neither as distinctive nor as

homogeneous as “ghetto” implied, and warned that academic theories of “ghetto”

life might “perpetuate the very stereotypes their proponents often aim to

fight.”

Mitchell Duneier seems to have taken Small’s pronouncement as a

challenge; his response is “Ghetto”

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux), a history of the concept which also serves as an

argument for its continued usefulness. Duneier is a sociologist, too, sensitive

to the sting of “ghetto” as an insult. But for him that sting shows us just how

much inequality we still tolerate, even as attitudes have changed. Where the

ghetto once seemed a menace, threatening to swallow the city like an

encroaching desert, now it often appears, in scholarly articles and the popular

press, as an endangered habitat. Academics and activists who once sought to

abolish ghettos may now speak, instead, of saving them. This shift, as much as

anything, accounts for the vigorous response to Tarantino’s comment: people

wanted to know just what was so bad about a ghetto, anyway.

In 1945, St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton published “Black Metropolis:

A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City.” When they wrote about a

“Black Ghetto” in Chicago, they were making a provocative analogy. Duneier

notes that, in explaining how blacks were prevented from buying or renting

homes in white neighborhoods, Drake and Cayton referred to “the invisible

barbed-wire fence of restrictive covenants,” a formulation that was calculated

to evoke gruesome images of the Third Reich. Despite the long history of Jewish

ghettos in Europe, Duneier is at pains to show that the Nazi ghetto was not a

revival of European history but a break from it. In the old Italian ghettos,

Jews, who were ostracized by authorities, created their own tightly organized

communities. The restrictions were onerous but not absolute; residents were

sometimes permitted to leave during the day and return at night. (Duneier

suggests that some inhabitants of the Roman ghetto might have viewed it as “a

holy precinct, its barriers recalling the walls of ancient Jerusalem.”) By

contrast, the Nazi version was a brutal, short-lived experiment. Duneier

describes the debate, among Nazi officials, between “productionists,” who saw

the inhabitants of Jewish ghettos as a useful source of slave labor, and

“attritionists,” who preferred them dead.

The modern history of American ghettos, then, begins with a

misunderstanding: the term acquired its awful resonance because of the Nazi

ghettos, even though the conditions in American cities more closely resembled

those of the older European ghettos, which were places capable of inspiring

mixed feelings, among both inhabitants and scholars. American ghettos were the

combined product of legal discrimination, personal prejudice, flawed urban

planning, and countless economic calculations. For more than thirty years,

starting in 1934, the Federal Housing Authority steered banks away from issuing

mortgages to prospective buyers in poor black neighborhoods, which were deemed

too risky; black tenants or prospective homeowners were often stymied by banks

that doubted their creditworthiness, or by deed requirements that sought to

maintain a neighborhood’s character and forbade blacks to buy or lease, or by

intimidation and violence. Disconcertingly, white homeowners who worried that

integration might erode the value of their homes may have been correct, even as

their decision to flee exacerbated the problem. Drake and Cayton described

their subjects as less bothered by segregation itself than by its stifling

effects. “They wanted their neighborhoods to be able to expand into contiguous

white areas as they became too crowded,” Duneier summarizes, “but they did not

actually care to live among whites.”

Scholars who studied the ghetto tended to be motivated by sympathy

for its residents, which often resulted in a complicated sort of sympathy for

ghettos themselves. Clark, making his study of Harlem, spent time with Malcolm

X, who insisted that segregation —“complete separation”—was the only way to

solve America’s problems. Clark didn’t go that far, but he did express a

certain skepticism about the wisdom and the prospects of school desegregation.

Better, he thought, to “demand excellence in ghetto schools,” as Duneier puts

it. Similarly, the anthropologist Carol Stack, in an influential 1974 book

called “All

Our Kin,” suggested that the black ghetto fostered social

coöperation, knitting its residents together in extended “networks” of families

and friends. At the same time, scholars sought to pin down the relationship

between “ghetto” and its Spanish-language analogue, “barrio,” and to compare

poor black neighborhoods with other enclaves. When an activist named Carl

Wittman announced, in 1970, “We have formed a ghetto, out of self protection,”

he was calling for a different kind of separatism: he was writing about his

adopted home town of San Francisco, in a pamphlet titled “A Gay Manifesto.”

Duneier’s book makes it easy to see how, through all these

changes, black ghettos in America have remained the central point of reference

for anyone who wants to understand poverty and segregation. By some estimates,

African-Americans are more isolated now than they were half a century ago. In a

study published last year, scholars at Stanford reported that even middle-class

African-Americans live in markedly poorer neighborhoods than working-class

whites. And the linguist William Labov has suggested that, during the past two

centuries, African-American speech patterns have been diverging from white

speech patterns, owing mainly to “residential segregation.” By many

measures—marriage rates, incarceration levels, wealth metrics—poor black

neighborhoods stand out.

Even so, Duneier’s review of the scholarly literature cannot

obscure the fact that the term “ghetto” does seem to have faded somewhat from

common usage. In the past decade or so, the adjective has overshadowed the

noun: a word that once conjured up intimidating neighborhoods now appears in

unintimidating coinages like “ghetto latte.” (This is a coffee-shop term

popularized in the aughts, in honor of the parsimonious customer who, instead

of ordering an iced latte, orders espresso over ice, which is cheaper, and then

dumps in half a cup of milk.) On hip-hop records, “ghetto” has largely given

way to the warmer, more flexible “hood,” which sounds less like a condition and

more like a community; Kendrick Lamar’s ode to the bad old days is called “Hood

Politics,” not “Ghetto Politics.” The persistence of residential segregation

has tightened the relationship between concentrated poverty and

African-American neighborhoods, and made the word “ghetto” harder to use.

“Ghetto” has come to sound like an indictment of a people as well as of a

place.

Our doubts about the word may also have something to do with our

changing view of cities. Many of the studies in Duneier’s book were conducted

in the shadow of white flight and, starting in the nineteen-sixties, rising

crime rates. The term suggested that a particular sort of dysfunction was

native to urban environments and, possibly, inseparable from them. But fewer

people talk about cities that way anymore: among contemporary urbanists, a

dominant influence is Jane Jacobs, known for her lifelong commitment to the

simple but radical notion that city life can be pleasurable. To judge from the

literature, the major preoccupation among today’s urbanists is not the ghetto but

a different G-word: “gentrification,” a process by which a ghetto might cease

to be a ghetto.

It is an inelegant term, and must have seemed a strange one when

it was first introduced, in a 1964 essay by Ruth Glass, a British sociologist.

Glass, who wrote under the influence of Marx, was distressed to see that “the

working class quarters of London have been invaded by the middle classes.” As

the gentry moved in, the proletariat moved out, “until all or most of the

original working class occupiers are displaced and the whole social character

of the district is changed.” The story of gentrification was, curiously, the

story of neighborhoods destroyed by desirability. As the term spread through

academic journals and then the popular press, “gentrification,” like “ghetto,”

became harder to define. At first, it referred to instances of new arrivals who

were buying up (and bidding up) old housing stock, but then there was

“new-build gentrification.” Especially in America, gentrification often

suggested white arrivals who were displacing nonwhite residents and taking over

a ghetto, although, in the case of San Francisco, the establishment of

Wittman’s so-called “gay ghetto,” created as an act of self-protection, was

also a species of gentrification. Even Clark’s “dark ghetto” was a target. In

1994, Andrew Cuomo, who was then at the Department of Housing and Urban

Development, told the Times, “If you expect to see Harlem as gentrified and

mixed-income, it’s not going to happen.” He was, in due course, proved wrong.

A gentrification story often unspools as a morality play, with

bohemians playing a central if ambiguous part: their arrival can signal that a

neighborhood is undergoing gentrification, but so can their departure, as

rising rents increasingly bring economic stratification. Stories of

gentrification are by definition stories of change, and yet scholars have had a

surprisingly hard time figuring out who gets displaced, and how. In 2004, Lance

Freeman, an urban-planning professor at Columbia, and the economist Frank

Braconi, who ran the Citizens Housing and Planning Council, tried to answer the

question. They produced a paper called “Gentrification

and Displacement: New York City in the 1990s,” which has been

roiling the debate ever since. In the paper, which was based on city survey

data, they came close to debunking the very idea of gentrification. Looking at

seven “gentrifying neighborhoods” (Chelsea, Harlem, the Lower East Side,

Morningside Heights, Fort Greene, Park Slope, and Williamsburg), they found

that “poor households” in those places were “19% less likely to move than poor

households residing elsewhere.”

While traditional gentrification narratives suggest that poor

residents, if not for the bane of gentrification, would have been fixed in

place, the truth is that poorer households generally move more often than

richer ones; in many poor neighborhoods, the threat of eviction is

ever-present, which helps explain why rising rents don’t necessarily increase

turnover. And gentrification needn’t be zero-sum, because gentrifying

neighborhoods may become more densely populated, with new arrivals adding to,

rather than supplanting, those currently resident. Freeman and Braconi

suggested that in some cases improved amenities in gentrifying neighborhoods

gave longtime residents an incentive to find a way to stay. At the same time,

New York’s rent-control and rent-stabilization laws have protected some tenants

from sharp rent increases, while others have an even more reliable refuge from

rising prices: subsidized apartments in city buildings. “Public housing, often

criticized for anchoring the poor to declining neighborhoods, may also have the

advantage of anchoring them to gentrifying neighborhoods,” they wrote. When two

scholars who took a dim view of gentrification, Kathe Newman and Elvin Wyly,

did their own investigation, their conclusion was mild. “Although displacement

affects a very small minority of households, it cannot be dismissed as

insignificant,” they wrote. “Ten thousand displacees a year”—this was one

estimate of New York’s total—“should not be ignored, even in a city of eight

million.”

Newman and Wyly’s paper was called “The Right to Stay Put,

Revisited,” in tribute to a decades-old question in urban sociology: Do tenants

have a political right—a human right—to remain in their apartments? In New

York, regulations like rent stabilization not only limit the amount by which

some landlords can raise rents but also restrict a landlord’s ability to

decline to renew a lease. In Sweden, the rules are tighter: rents are set

through a national negotiation between tenants and landlords, which means that

prices are low in Stockholm, but apartments are scarce; a renter in search of a

longterm lease there might spend decades on a government waiting list. Another

solution is to allow more and taller buildings, increasing supply in the hope

of lowering prices. Often, the steepest rent increases are found in places,

like San Francisco, that have stringent building regulations: a recent study of

the city found that fewer poor residents had been displaced in neighborhoods

with more new construction. In seeking to preserve what Ruth Glass called the

“social character” of a neighborhood, antigentrification activists echo the

language that was once used to defend racially restrictive covenants. Arguments

over gentrification are really arguments over who deserves to live in a city,

and the notion of a right to stay put is sometimes at odds with another,

perhaps more fundamental right: the right to move.

Earlier this year, in the pages of National Review, Kevin D.

Williamson devoted a typically astringent column to the kind of poor community

that is rarely called a ghetto and even less often targeted for gentrification.

A fellow-pundit had suggested that Donald Trump, unlike many other Republican

politicians, spoke to and for white voters living lives of economic frustration

and opioid dependency in towns like Garbutt, New York. Williamson, no fan of

Trump, responded with a withering attack on Garbutt and its ilk. “The truth

about these dysfunctional, downscale communities is that they deserve to die,”

Williamson wrote. Their inhabitants, in his view, “need real opportunity, which

means that they need real change, which means that they need UHaul.”

This diagnosis sparked an outcry. But was Williamson wrong to

insist that people are more important than places? Arguments about gentrification

sometimes imply that places matter most. Jane Jacobs, for instance, could seem

to cherish Greenwich Village more than she cherished the people who lived

there, to say nothing of the people who might have liked to join them, if only

there had been more and cheaper housing. When it comes to the neighborhoods

that Duneier would call ghettos, there is some evidence that the most humane

approach is not to improve them but, in effect, to dismantle them, by

encouraging their inhabitants to move. A program called Moving to Opportunity,

which was initially judged a failure, now provides modest evidence that

removing children from high-poverty neighborhoods can have lasting positive

effects on their lifetime earnings. And a recent study by Deirdre Pfeiffer, a

professor of urban planning, suggests that racial minorities encounter “more

equitable” conditions in newly built suburbs than in cities.

The uneasy way we discuss ghettos and gentrification says

something about our discomfort with the real-estate market, which translates

every living space into a commodity whose value lies mainly outside our

control. Things that happen across the street, down the block, or on the other

side of town affect the worth of our homes, and this lack of control is predestined

to frustrate capitalists and community organizers alike. “Bushwick is not for

sale!” Letitia James, New York City’s Public Advocate, announced at a recent

anti-gentrification protest in Brooklyn. She was hoping to get the city to

force developers to set aside more units for low-income families, but she was

also voicing a familiar and widely shared distaste for the way the character of

a neighborhood is hostage to its market price. The opposite of gentrification

is not a quirky and charming enclave that stays affordable forever; the

opposite of gentrification is a decline in prices that reflects the

transformation of a once desirable neighborhood into one that is looking more

like a ghetto every day.

In a recent Times Op-Ed, the Harlem historian Michael Henry Adams

lamented the changes in his neighborhood, complaining that “poor black

neighborhoods” were “irresistible to gentrification.” But New York is an

unusual place, and it’s possible that the conversation about gentrification has

been distorted by our focus on neighborhoods like Harlem. A recent study found

that Chicago neighborhoods that were forty per cent or more African-American

were the least likely to experience gentrification. This statistic was cited by

the journalist Natalie Y. Moore in her new book about her city, “The South Side.”

She recounts the pride she felt when she bought a condo in a seemingly

up-and-coming South Side neighborhood: she paid a hundred and seventy two

thousand dollars, and she was shocked when, five years later, an assessor told

her that its value had depreciated to fifty-five thousand. She writes about

herself as a “so called gentrifier,” adding, ruefully, that “black Chicago

neighborhoods don’t gentrify.”

In May, on CNN, the comedian W. Kamau Bell hosted a one-hour program

about gentrification in Portland, Oregon. He has a keen eye for irony and a

high tolerance for awkward situations, so he walked around the city, chuckling

at hipsters—a word at least as hard to define as “ghetto” or

“gentrification”—and listening sympathetically to residents of the city’s

dwindling African-American neighborhoods. An older woman named Beverly said

that her neighborhood was gone; standing on the porch of her mauve-trimmed

house, she gestured across the street at a new apartment building going up,

which seemed likely to ruin her lovely view. To hear the other side, Bell met

with Ben Kaiser, a local developer, who was unapologetic. Bell told him, “I

talked to an older black woman in this neighborhood, and every so often

somebody knocks at her door or calls her and is offering to buy her home, even

though she’s made it clear that she wants to keep her home. And somebody’s

telling them to make that phone call.”

“We always think it’s a somebody, and in my opinion it’s an

economic force—there’s no one orchestrating this outcome,” Kaiser said. “What’s

happened, historically, is they’re offered a tremendous amount of money, and

they’re kind of nuts not to take it. At some point, her kids—or she—will say,

‘I am nuts not to take this offer.’ ”

Bell was unconvinced. He wasn’t sure how many new “twelve-dollar

juice bars” and “high-end vegan barbecue” restaurants the neighborhood needed,

and he worried that the old neighborhood wouldn’t survive. In the ghetto

narrative, a poor neighborhood falls victim to isolation; in the gentrification

narrative, a poor neighborhood falls victim to invasion. These stories are not

necessarily contradictory—they reflect a common conviction that the sorrows and

joys of neighborhood change tend to be unequally shared. One effect of

gentrification is to make this inequality harder to ignore. The call to save a

neighborhood is most compelling when it serves as a call to help a

neighborhood’s neediest inhabitants. That might mean helping them stay. But it

might also mean helping them leave.

*An earlier

version of this article incorrectly stated that Jews in sixteenth-century

Venice were confined to the ghetto by papal decree. The papal decree applied to

Jews in Rome.

Kelefa

Sanneh has contributed to The New Yorker since 2001.

This article

appears in other versions of the July 11 & 18, 2016, issue, with the

headline “There Goes the Neighborhood.”

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/07/11/is-gentrification-really-a-problem

Monday, July 25, 2016

Do Words Kill? - Exhibition at LA Central Library

Learning what propaganda is and how to

counter it is essential in today’s information-saturated world. The special

exhibition “State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda” produced by the

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, explores how the Nazis used propaganda

to win broad voter support in Germany, implement radical programs, and justify

was and mass murder.

LA Central Library, Gerry Gallery, 5th Street,

Los Angeles, from March 10th – until August 21st. #StateofDeception

Monday, July 18, 2016

Reservation Required @ Disneyland

Due to the overwhelming popularity of restaurants with table

service at Disneyland – reservations are required. It was a bit of a shock to see that

reservations where required at the Carnation Café, but we were able to obtain a

table in the sun after a 20 minute wait (which I don’t recommend). If you are planning to visit Disneyland, good

idea to book your dining plans by calling the “Disney Dine Line” at 714-781-3463

and reserve your table.

Thursday, July 14, 2016

Children Are Evil - Tame Them With Jedi Mind Tricks

by Chelsea Leu

Kids are master manipulators. They play up their charms, pit adults against one another, and engage in loud, public wailing. So it's your job to keep up with them, Carnegie Mellon's Kevin Zollman says. His new book, The Game Theorist's Guide to Parenting - written with journalist Paul Raeburn - explains how.

FORCE COOPERATION

For siblings who refuse to work together, Zollman recommends a version of the prisoner's dilemma. Assign them a task they can do jointly, like picking up the toys, then give them each the same reward or punishment based on their performance as a team: If one kid slacks off, the next time around the other one is likely to refuse to cooperate, and both will lose out. Over time, this setup compels teamwork.

MAKE THEM PAY

Who gets the bigger room? Who gets to name the cat? It's the old King Solomon problem: Somethings you just can't cut in half. So have kids bid with chores or their allowance. If one of them wants to name the cat Macaroni & Cheese, he'll have to pay for it.

THREATEN THEM - FOR REAL

Screaming "Don't make me turn this car around!" never works. That's what Zollman calls a noncredible threat-kids see through it, because they know it means you'll suffer too. So pick punishments that benefit you. Like: "Stop punching your sister or we're going to Grandma's instead of the movies."

MAKE THEM LIE

If you suspect your kids haven't done their homework, nail them with specific questions: Which subject? What did you learn? How long did it take? Hardest part? Even if they manage convincing answers, the act of sustaining an elaborate lie exerts psychological discomfort. Eventually they'll figure out that being honest is just easier.

DON'T BAIL THEM OUT

To make all these lessons stick, you have to buckle down. If your kid's in a bit of trouble and sobbing pitifully, resist the urge to swoop in and save her by remembering something economists call moral hazard. Corporate bailouts incentivize bad behavior - avoid this fate by establishing clear rules and meting out punishment when necessary.

Sunday, June 26, 2016

Health Checklist - Your Guide to 9 Basic Diabetes Tests and Screenings For Adults

by Allison Tsai

1. A1C / eAG

WHAT TO EXPECT: Your health care provider will test your blood to measure your average blood glucose level over the past few months. A high reading can indicate that your diabetes is not well controlled. Sometimes AlC results are shown as an estimated average glucose, or eAG, which is translated into the kind of mg/dl reading you see on your meter.

TARGET: Generally less than 7 percent for A1C and less than 154 mg/dl for eAG. You may have lower or higher targets based on factors such as your age and other medical conditions.

HOW OFTEN: Twice a year if your A1C is in your target range. If your A1C is off target or you're adjusting medications or other treatments, this test is recommended four times a year.

2. Dilated Eye Exam

WHAT TO EXPECT: An ophthalmologist or an optometrist will put drops in your eye to dilate the pupil and then use magnifying equipment to look at the retina, the tissue in the back of the eye that sends the images we see to the brain. This screens for diabetic retinopathy, which includes changes to the retinal blood vessels and can damage vision.

HOW OFTEN: At the time of diagnosis for people with type 2 and within five years of diagnosis for those with type 1. If annual eye exams are clear for at least two years, then exams may be appropriate every two years. If any level of retinopathy is detected, an eye exam should be done at least once a year.

A HOME CARE: Control your blood glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure to help lower the risk of retinopathy.

3. Blood Pressure

WHAT TO EXPECT: A cuff is a wrapped around your upper arm and inflated to measure your blood pressure. High blood pressure can lead to heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease.

TARGET: Less than 120/80 mmHg is ideal, but people taking blood pressure medication should aim for less than 140/90 mmHg. If your blood pressure is over 120/80 mmHg and you're not on medication, your doctor will recommend lifestyle changes such as improving fitness, losing weight, and eating a healthful diet. If your blood pressure is over 140/90 mmHg, your doctor may prescribe blood pressure medication.

HOW OFTEN: Every doctor visit.

4. Cholesterol

WHAT TO EXPECT: A fasting blood test will measure fats in your blood: LDL, HDL, and triglyceride levels.

ACTION POINTS:

LDL ("bad") cholesterol can stick to artery walls and raise your risk for heart attack and stroke. Are you between the ages of 40 and 75? If you don't have other heart disease risk factors, your doctor will likely recommend a moderate-intensity statin and healthier lifestyle. If you have heart disease, you may need high-intensity statin treatment.

HDL ("good") cholesterol is carried in particles that help remove bad cholesterol from the artery walls and reduce the risk of heart disease. If levels are below 40 mg/dl in men or below 50 mg/dl in women, your doctor may encourage you to step up healthy eating and exercise to increase HDL.

Triglycerides are a measure of fat in the blood and help LDL cholesterol harm the arteries. If your level is 150 mg/dl or higher, your doctor may recommend lifestyle changes, including improved fitness and nutrition. Better blood glucose control may also lower triglyceride levels.

5. Serum Creatinine/eGFR

WHAT TO EXPECT: This test, which measures a specific protein in the blood, screens for kidney disease and monitors its progression.

ACTION POINT: In general, if your estimated GFR is less than 60 ml/min/1.73m2, your kidney function is abnormally low, and your doctor will begin to look for the cause of the decline. If the cause is diabetic kidney disease, medication and better blood glucose and blood pressure control might slow the progre_ssion of kidney damage.

HOW OFTEN: At least once a year if you have high blood pressure, if you have type 2 diabetes, or if you've had type 1 diabetes for five years or more.

HOW OFTEN: It does depend, but at least every five years. Talk to your doctor about when to get your next cholesterol test.

6. Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio

WHAT TO EXPECT: Using your urine sample, this test screens for kidney disease and monitors its progression.

ACTION POINT: If your results are greater than 30 mg/g and the cause is diabetic kidney disease, using certain medications and improving blood glucose and blood pressure control may slow the progression of kidney damage.

HOW OFTEN: At least once a year if you have high blood pressure, if you have type 2 diabetes, or if you've had type 1 diabetes for five years or more.

7. Foot Evaluation

WHAT TO EXPECT: Your doctor will inspect your feet for any abrasions, ulcers (open sores), wounds, and signs of nerve damage (neuropathy), such as loss of ankle reflexes and loss of sensation in your feet and toes. ·

HOW OFTEN: Once a year -or- more, if you are at high risk for foot problems, such as if you've had an ulcer in the past, have decreased sensitivity, or have peripheral artery disease (PAD).

HOME CARE: Inspect your feet between doctor exams. If you are unable to see the bottoms of your feet, put a mirror on the floor to check them, or ask someone who knows what to look for to check the bottoms of your feet on a daily basis.

8. Ankle-Brachial Index

WHAT TO EXPECT: Your doctor will use an inflatable cuff to measure your blood pressure at your arm and ankle to check for PAD. The condition occurs when arteries in the limbs narrow and reduce circulation, increasing the risk for heart attack, stroke even amputation, if PAD is severe. Testing should be done in patients with symptoms of PAD, including decreased walking speed, leg fatigue, cramping pain brought on by exercise, and the absence of a pulse in the foot.

ACTION POINT: According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, a normal result is between 0.9 and 1.3, which is determined by comparing the blood pressure at your arm with that at your ankle. If your results are lower than that range, your doctor may discuss treatment options.

9. Body Mass Index

WHAT TO EXPECT: Step on the scale and stand tall. Your weight and height will be recorded at your visit. Body mass index (BMI) is calculated as a ratio of weight to height and is used to determine if you are overweight or obese.

ACTION POINT: If your BMI is above 24.9, your doctor may discuss weight-loss options. If you have type 2 diabetes and a BMI of 27 or greater, you may be a candidate for weight-loss medications. If you have type 2 and your BMI is greater than 35, you may be considered for bariatric surgery. The risk for weight-related health problems rises with increasing BMI.

HOW OFTEN: Every doctor visit

Diabetes Forecast, July/August 2016

1. A1C / eAG

WHAT TO EXPECT: Your health care provider will test your blood to measure your average blood glucose level over the past few months. A high reading can indicate that your diabetes is not well controlled. Sometimes AlC results are shown as an estimated average glucose, or eAG, which is translated into the kind of mg/dl reading you see on your meter.

TARGET: Generally less than 7 percent for A1C and less than 154 mg/dl for eAG. You may have lower or higher targets based on factors such as your age and other medical conditions.

HOW OFTEN: Twice a year if your A1C is in your target range. If your A1C is off target or you're adjusting medications or other treatments, this test is recommended four times a year.

2. Dilated Eye Exam

WHAT TO EXPECT: An ophthalmologist or an optometrist will put drops in your eye to dilate the pupil and then use magnifying equipment to look at the retina, the tissue in the back of the eye that sends the images we see to the brain. This screens for diabetic retinopathy, which includes changes to the retinal blood vessels and can damage vision.

HOW OFTEN: At the time of diagnosis for people with type 2 and within five years of diagnosis for those with type 1. If annual eye exams are clear for at least two years, then exams may be appropriate every two years. If any level of retinopathy is detected, an eye exam should be done at least once a year.

A HOME CARE: Control your blood glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure to help lower the risk of retinopathy.

3. Blood Pressure

WHAT TO EXPECT: A cuff is a wrapped around your upper arm and inflated to measure your blood pressure. High blood pressure can lead to heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease.

TARGET: Less than 120/80 mmHg is ideal, but people taking blood pressure medication should aim for less than 140/90 mmHg. If your blood pressure is over 120/80 mmHg and you're not on medication, your doctor will recommend lifestyle changes such as improving fitness, losing weight, and eating a healthful diet. If your blood pressure is over 140/90 mmHg, your doctor may prescribe blood pressure medication.

HOW OFTEN: Every doctor visit.

4. Cholesterol

WHAT TO EXPECT: A fasting blood test will measure fats in your blood: LDL, HDL, and triglyceride levels.

ACTION POINTS:

LDL ("bad") cholesterol can stick to artery walls and raise your risk for heart attack and stroke. Are you between the ages of 40 and 75? If you don't have other heart disease risk factors, your doctor will likely recommend a moderate-intensity statin and healthier lifestyle. If you have heart disease, you may need high-intensity statin treatment.

HDL ("good") cholesterol is carried in particles that help remove bad cholesterol from the artery walls and reduce the risk of heart disease. If levels are below 40 mg/dl in men or below 50 mg/dl in women, your doctor may encourage you to step up healthy eating and exercise to increase HDL.

Triglycerides are a measure of fat in the blood and help LDL cholesterol harm the arteries. If your level is 150 mg/dl or higher, your doctor may recommend lifestyle changes, including improved fitness and nutrition. Better blood glucose control may also lower triglyceride levels.

5. Serum Creatinine/eGFR

WHAT TO EXPECT: This test, which measures a specific protein in the blood, screens for kidney disease and monitors its progression.

ACTION POINT: In general, if your estimated GFR is less than 60 ml/min/1.73m2, your kidney function is abnormally low, and your doctor will begin to look for the cause of the decline. If the cause is diabetic kidney disease, medication and better blood glucose and blood pressure control might slow the progre_ssion of kidney damage.

HOW OFTEN: At least once a year if you have high blood pressure, if you have type 2 diabetes, or if you've had type 1 diabetes for five years or more.

HOW OFTEN: It does depend, but at least every five years. Talk to your doctor about when to get your next cholesterol test.

6. Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio

WHAT TO EXPECT: Using your urine sample, this test screens for kidney disease and monitors its progression.

ACTION POINT: If your results are greater than 30 mg/g and the cause is diabetic kidney disease, using certain medications and improving blood glucose and blood pressure control may slow the progression of kidney damage.

HOW OFTEN: At least once a year if you have high blood pressure, if you have type 2 diabetes, or if you've had type 1 diabetes for five years or more.

7. Foot Evaluation

WHAT TO EXPECT: Your doctor will inspect your feet for any abrasions, ulcers (open sores), wounds, and signs of nerve damage (neuropathy), such as loss of ankle reflexes and loss of sensation in your feet and toes. ·

HOW OFTEN: Once a year -or- more, if you are at high risk for foot problems, such as if you've had an ulcer in the past, have decreased sensitivity, or have peripheral artery disease (PAD).

HOME CARE: Inspect your feet between doctor exams. If you are unable to see the bottoms of your feet, put a mirror on the floor to check them, or ask someone who knows what to look for to check the bottoms of your feet on a daily basis.

8. Ankle-Brachial Index

WHAT TO EXPECT: Your doctor will use an inflatable cuff to measure your blood pressure at your arm and ankle to check for PAD. The condition occurs when arteries in the limbs narrow and reduce circulation, increasing the risk for heart attack, stroke even amputation, if PAD is severe. Testing should be done in patients with symptoms of PAD, including decreased walking speed, leg fatigue, cramping pain brought on by exercise, and the absence of a pulse in the foot.

ACTION POINT: According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, a normal result is between 0.9 and 1.3, which is determined by comparing the blood pressure at your arm with that at your ankle. If your results are lower than that range, your doctor may discuss treatment options.

9. Body Mass Index

WHAT TO EXPECT: Step on the scale and stand tall. Your weight and height will be recorded at your visit. Body mass index (BMI) is calculated as a ratio of weight to height and is used to determine if you are overweight or obese.

ACTION POINT: If your BMI is above 24.9, your doctor may discuss weight-loss options. If you have type 2 diabetes and a BMI of 27 or greater, you may be a candidate for weight-loss medications. If you have type 2 and your BMI is greater than 35, you may be considered for bariatric surgery. The risk for weight-related health problems rises with increasing BMI.

HOW OFTEN: Every doctor visit

Diabetes Forecast, July/August 2016

Wonderful Summer Lemonade

Sugar Woes

Sugary sodas are unhealthful for many reasons: They raise blood glucose in people with diabetes, and they can lead to heart disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Unfortunately, nearly one in three Americans still drink at least one sugar-sweetened beverage (not including 100 percent fruit juice) per day, according to a nationwide survey of 157,668 adults. People between the ages of 18 and 24, men, African American adults, the unemployed, and those with less than a high school education were most likely to down the sugary drinks. A better option: quench your thirst with water.

source: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, published online Feb. 26, 2016

Wonderful Summer Lemonade

(under 150 Calories)

Makes: 6

Serving Size: 1 cup

Preparation Time: 7 minute

Ingredients

1 cup water

1/3 cup Splenda

1 cup fresh lemon juice (from 4 to 6 fresh lemons), or more for added tartness

4 cups cold water

Fresh mint sprigs for garnish

Directions:

- In a small saucepan, combine the water and Splenda. Bring to a gentle boil to dissolve the Splenda.

- Add the sweetened water to a pitcher, and pour in the lemon juice. Fill the pitcher with the 4 cups of cold water. Refrigerate for 30 minutes.

- Taste and correct sweetness if necessary. Serve over ice cubes. Garnish with mint.

PER SERVING

Serving Size: 1 cup

Calories 15

Fat 0g

Saturated Fat 0g

Trans Fat 0g

Carbohydrate 4g

Fiber 0g

Sugars 2g

Cholesterol 0mg

Sodium 15 mg

Protein 0g

Friday, May 06, 2016

WORKING-CLASS HEROES by Jelani Cobb

During the 2008 Vice-Presidential debate between Joe Biden and Sarah Palin, in St. Louis, Biden offered a memorable brief on behalf of struggling communities like the one in Pennsylvania where he spent his childhood. Biden, whose common-man bona fides were seen as an antidote to Barack Obama's Ivy League credentials and relative aloofness, spoke evocatively of the pain felt by a portion of America that is more usually described in the gauzy, romantic tones of American greatness. "Look, the people in my neighborhood, they get it," Biden said. "They know they've been getting the short end of the stick. So walk with me in my neighborhood, go back to my old neighborhood, in Claymont, an old steel town, or go up to Scranton with me. These people know the middle class has gotten the short end. The wealthy have done very well. Corporate America has been rewarded. It's time we change it."

In hindsight, what's notable about Biden's statement is not how it presaged the populist concerns of this year's Presidential election but the fact that he referred to his neighbors-steelworkers, denizens of factory towns - as middle class, not as working class. In fact, the phrase "working class" came up twice during the debate - but it was Palin who said it, not Biden. Things didn't change much rhetorically in the 2012 election. Obama and Mitt Romney, in the course of three Presidential debates, invoked the "middle class" forty-three times but never mentioned the proletariat.

For decades, both American culture and American politics have elided the differences between salaried workers and those who are paid hourly, between college-educated professionals and those whose purchasing power is connected to membership in a labor union. Some ninety percent of Americans, including most millionaires, routinely identify as middle class. For many years, this glossing over of the distinctions between the classes served a broad set of interests, particularly during the Cold War, when any reference to class carried a whiff of socialist sympathies. Americans considered themselves part of a larger whole, and social animosities were mostly siphoned off in the direction of racial resentment. But, this year, Americans are once again debating class.

We are clearly out of practice. The current language of "income inequality" is a low-carb version of the Old Left's "class exploitation. "The new phrase lacks rhetorical zing; it's hard to envision workers on a picket line singing rousing anthems about "income inequality." The term lacks a verb, too, so it's possible to think of the condition under discussion as a random social outcome, rather than as the product of deliberate actions taken by specific people. Bernie Sanders has tended to frame his position as a defense of an imperiled middle class, but he has also called out the "greedy billionaires" and "Wall Street"-a synecdoche for exploitation in general.

Donald Trump's populist appeals are all the more remarkable given that the modern Republican Party has been the largest beneficiary of this collapsing of class interests. Ever since Ronald Reagan's Presidency, progressives have pondered why working-class and poor whites vote Republican, against their own interests. The fact that the charge is being led on the right by a billionaire real-estate developer, however, suggests that the new recognition of class is not without its contradictions. It's also worth noting that Romney, the man leading the attempt to quell this populist uprising, on behalf of the Party's alarmed establishment, is a multimillionaire who lost the previous election, in part, because he dismissed forty-seven percent of Americans as "freeloaders."

Strikingly, the emerging dialogue on class is informed by the ways in which we have typically talked about race. In 1976, the majority of welfare recipients in the United States were not black. But when, during the Presidential campaign that year, Reagan made his famous comments about the "welfare queen," they were widely taken to mean that the problem wasn't poor people in general but, rather, certain blacks in inner cities, who were purportedly cheating the system (and whose votes the Republican Party had already jettisoned). Today, in the battle over, say, public-sector unions, it's hard not to hear an echo of those complaints about social parasitism, though when Governor Scott Walker, of Wisconsin, campaigned to strip most public-sector unions of their collective-bargaining rights he did so in the language of Madison progressivism: "We can no longer live in a society where the public employees are the haves and taxpayers who foot the bills are the have-nots."

There are other hints that the old stereotypes about inner-city blacks are beginning to be deployed against working-class whites. Heightened mortality rates among middle-aged working-class whites and the concomitant spike in opioid addiction have, on the whole, generated sympathetic examinations of social displacement, in which addiction is seen as a public-health concern symptomatic of the changing economy, as opposed to a sign of moral failure. But, last month, in National Review, Kevin Williamson wrote:

The truth about these dysfunctional, downscale communities is that they deserve to die. Economically, they are negative assets. Morally, they are indefensible. Forget all your cheap theatrical Bruce Springsteen crap. Forget your sanctimony about struggling Rust Belt factory towns… The white American underclass is in thrall to a vicious, selfish culture whose main products are misery and used heroin needles. Donald Trump's speeches make them feel good. So does OxyContin.

These are the communities that Biden spoke of in 2008. Yet, according to Williamson, the apt metaphor isn't getting the short end of the stick but dropping the ball. In 2010, Charles Murray published "Coming Apart," a lamentation on the decline among poor whites of religiosity, of the work ethic, and of family values. It received just a fraction of the attention paid to his 1994 book, "The Bell Curve," which argued that a supposed intellectual inferiority factored into the plight of poor blacks. But in 2016 there is a new market for the ideas in "Coming Apart. "The fact that we are examining class may be novel, but it is almost certain that what we'll hear said about poverty won't be.

-Jelani Cobb

The New Yorker, 25 April 2016

Saturday, April 09, 2016

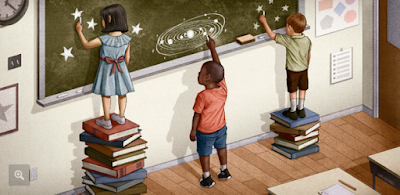

Why Talented Black and Hispanic Students Can Go Undiscovered by Susan Dynarski

"Researchers found that teachers and parents were less likely to refer high-ability blacks and Hispanics, as well as children learning English as a second language, for I.Q. testing. Multiple factors could be at work here: Teachers may have lower expectations for these children, and their parents may be unfamiliar with the process and the programs. Whatever the reason, the evidence indicates that relying on teachers and parents increases racial and ethnic disparities."

http://nyti.ms/1SEVOxS

http://nyti.ms/1SEVOxS

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)